We’re back with Yannick Boquin for round two of our interview. If you missed the first part of the interview, catch it here – if not read on. Yannick has spent time in pretty much all of the corners of the ballet world. Whether as a principal dancer, guest teacher, ballet master, or choreographer, he’s done it all, and in this section we explore some of the insights he’s come away with during each of these careers.

Once again: I’m assuming prior knowledge of the layout and function of a ballet class. If you need a primer, or even if you’re just interested, here’s a video of San Francisco Ballet’s company class. Skip forward to about 5 minutes in for the real start:

- Lucas: So you’ve taught, everywhere, as I’ve previously mentioned. When did you start teaching?

- Yannick: Two years before I quit ballet. I stopped when I was 38, so at 36 I was already teaching.

- L: And what has developed in your teaching? What are the things that you started out doing that you see now were a mistake? Like you were saying, your idea of technique has evolved through what you’ve seen and learned in other companies. How has that changed and adapted through the years?

- Y: I would say that my steps are less complicated. When you start something new, you think you’re going to start a worldwide revolution. I spoke with other teachers, and some of them thought the same. But the steps are what they are, and there’s nothing you can invent. [Yannick has much more to say on this topic, and this will be included in an extra feature if there’s interest.]

- As a ballet teacher right? Because as a choreographer…

- Oh yeah. That’s different. You can roll on the floor, you can do so many things.

- You can do that in ballet class, no? 😉

- Well, I don’t know if the next day I would have so many people in the class. I might have a problem.

- I suppose it depends on where you teach. 🙂 How have you changed your teaching habits in terms of the way you structure your class in order to make it as effective and inspiring as possible for the dancers?

- Well, I started to teach while I was still dancing and therefore, I could easily ask my friends their advice to improve my teaching. I also spent a lot of time, like 6 months with the pianist in Berlin, talking about musicality. So, I would have feedback from the pianist and from the dancers, which was very important, because today I simply cannot ask anything like that to anyone. As a teacher I can’t ask their opinion about my class, it just can’t be. Of course by now, I know that dancers appreciate my teaching, but it doesn’t stop me from questioning and exchanging thoughts and experiences to keep improving. In terms of structure, I just did it the way I would have liked to have it for myself as a dancer with the added influence of some teachers I had in my career. Then I guess that my school, my style, my combinations, and the fact that I tried my very best to be there for everyone is probably what makes it work.

- Why do you feel like you shouldn’t or can’t receive feedback from dancers nowadays?

- Well, the thing is that my generation of dancers is not dancing anymore. They became either directors, ballet masters or choreographers, or they do something else. Obviously dancers won’t criticize my class to my face. If they don’t like my work, they will just go to another class, and the others who do appreciate my class will show their appreciation afterwards, by some comments here and there. Anyway, you will never be able to please everyone. And by listening and talking with dancers, it is easy to know their needs and to work around that. But from my side, I simply can’t ask for straight feedback from dancers about the class, it just feels wrong.

- It’s like there’s some distance in the roles.

- Yeah. It’s like a choreographer cannot really ask a dancer “Did you like my choreography?” He’s the choreographer setting a piece for the company – at some point there’s a barrier that I feel like I cannot pass.

- Interesting. I understand that there’s that distance, but I’m not sure that it needs to be there. Maybe in some ways it’s a good thing. They do say a boss shouldn’t be friends with his employees, and in a way you’re our boss. You’re like our three-weeks-a-year boss.

- In a way. Not a boss boss, but I see what you mean. When I was a ballet master in Vienna, I had just left Berlin as a dancer, and I had friends from Berlin in the company there. And I remember very well one of them. I would be watching a rehearsal and he would come and sit next to me and give me a slap on the back and say “So, how are you my friend?” in front of everyone, 60 people in front of me. And this didn’t look right. I didn’t like it and I told him. I said “Don’t do that.” He said “Why? Come on, you know me…” I said “Because it’s not the place, it’s not the time.”

- This is the office.

Photo credit: Costin Radu - Exactly. It’s the office. I was going out with some dancers, and because you get close to them they feel like they can act differently the next day in rehearsal.

- You feel like you lose some of your authority.

- Yes. Even if they still respect your work and all that, somehow there is this personal thing that comes along, and I didn’t like that. Because I had just stopped dancing, they felt like they were very close to me. I was close to them and I was still young, but my position wasn’t the same anymore within the theater, even if everything was the same outside the studio.

- Interesting. As your role changes, your way of relating to the people around you is also affected. It has to change, because even if you want to be their friends and have that friendly demeanor, it may not work when you need to be their boss, or when you need to give them corrections, or be hard on them.

- Yes, but just with some of them. I just had a few bad experiences. But I must say, for example yesterday I went fishing with two dancers from this company, dancers that I’ve known for 15 years, since they were starting their careers in Antalya, and along the years I saw them in different places, in Lisbon, Istanbul, Monte Carlo. I even choreographed a ballet on one of them, so we are very close. Somehow, with some dancers there’s no problem. I can go fishing, and we didn’t just do it yesterday, every year we go fishing. But then the next day you can give a hug before the class, after the class, no problem. But with Melih, or Ediz, in class or in rehearsal, I can give a correction and they will just apply it. It won’t be a problem.

- So they respect your role, even as friends outside the studio.

- Yes. And yesterday we had a good laugh. No fish, but a good laugh. But today I expect them to work. And that’s fine, because I know I can do that with them.

- That’s, I think, a good thing to do, to be able to compartmentalize.

- Yes it is and I am expecting the dancers that I see outside of work to do the same. If they can’t… 😦

- Let’s talk about your choreography. In 2011 you choreographed your first ballet, an interpretation of Werther by Goethe. How was your approach to choreography, compared to creating exercises for a class?

- Well, I wouldn’t say it was like bringing a class onstage, but the coordination that I use in class was there – I kept it academic.

- So you wanted to stay very classical.

- Yes. But still, I did some things that I wouldn’t do in a class, of course. I did some solos – it’s a big love story about a man in love with a woman, Charlotte, already married to a man named Albert, taking place over a year and a half. He’s madly in love, can’t have her, and at the end he commits suicide.

- Okay, so suicide is one of the things that happened in your ballet that would never happen in your class…

- Thank God, NO! Of course in this love story, I had to put some arms and interpretations in the solos.

- We’re talking about mime to tell the story.

- Yes, using his arms in a free way, fists, etc… to tell emotions, you know.

- So… emotion. This is where you have to leave technique – in order to say something.

Werther has a rough time in this ballet. Photography: Inci Ozbas - Yes. I did this ballet for Istanbul, then two years later I did it for the Greek National Ballet in Athens. I made some changes, choreographically, and if I do it again I will make some more, because I’m never happy with what I do.

- Spoken like a true ballet dancer.

- Yeah, but I’m still waiting to do it somewhere else where I could finally do the right costumes, setting, and lighting.

- So, throughout this interview we’ve seen that you’re a true perfectionist, you really demand perfection from yourself and others. What would you say to dancers that are never happy with their own work?

- I would say don’t put the barre so high, because if you cannot reach it you will never be happy and that will go against you. I was also like that as a dancer. I wanted to have split jetés, I wanted to have higher jumps, I wanted to do this and that. Physically, I couldn’t reach that, so I was never really satisfied. But it is possible to have a certain perfection even if you’re not that high in your jump, or if you’re not as flexible as you’d like to be, and you should try to reach for that perfection with whatever is in your possession, keeping in mind your possibilities and limits.

- But usually I would say that our idea of what we should be able to do exceeds our actual ability. You may be able to do a split jump as coordinated as you can do it, but it may not actually satisfy you.

- Yeah, and this is why you should know where to put the barre. A beautiful grand jeté doesn’t have to be in a split, especially for male dancers.

- Know your boundaries.

- If this is what you can do – of course we can always do better – that’s a nice thing to say, but sometimes you cannot do any better with what you have. When you’re young you can work on your flexibility and technique but at some stage of your career and with age, it gets to a point where your back can only bend so much, your leg can’t go any higher and your jump isn’t as high as it was before. When you are young, you just go for it. You’re like a young horse – you are free in the fields, you run and you don’t think, you just go. You’re fearless and you have the energy to try more and more, you hate the weekend, you want to be in the studio all the time. I was like that. Then, a bit later on, I started to put the barre very high, a barre that I couldn’t always reach. In a way it was good because I always demanded more from myself, but on the other hand I was never really satisfied.

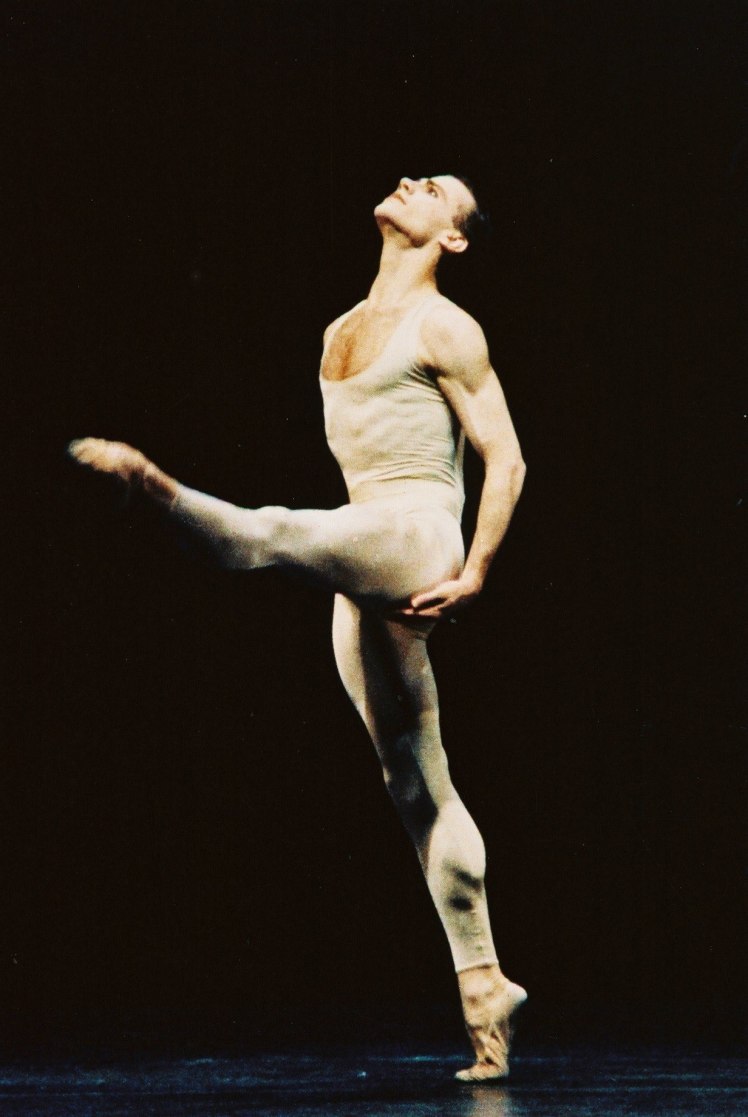

Yannick, with all that he had. It was a lot. From the ballet Proust, from Roland Petit. Photo credit: Kranich - So when did you learn that you had what you had and to accept that?

- It was in my late thirties, when my body slowly couldn’t respond anymore the way I wanted. This is when I knew that the technique I had was what it was, and that I would have to maintain it till the end of my career to the best I could.

- And how did that acceptance change the way you felt about what you did? Did that make you more content as you were dancing? Did you appreciate the journey more?

- Yes. I was approaching my rehearsals and performances on another level, and if things didn’t go well, I wouldn’t let them affect me the way it did in the past. I didn’t want to be the one – probably the only one – remembering things that might have gone wrong during the show. In my twenties, I had a serious back injury and four surgeries on my foot and knee, and for some of them I had to fight so much to come back. But I always did, and I learned so much from these experiences. I became much stronger mentally and that helped me to approach what I call my second career, when I entered my thirties. The barre that I had placed so high in the past became reachable because I had finally learned to deal with what I had. I did appreciate the journey more, although you realize that something’s leaving you. The energy and all that is not the same.

- You feel your age. There’s a reason that ballet dancers tend to retire in their 30’s.

-

And that’s a shame because this is really the best time. You gained so much knowledge and experience along the years, and that’s when you want to be able to use all of that. But the physicality and the strength are slowly letting you down and that is really upsetting. You just have to keep going on a different level, but it’s great once you’ve accepted it – and I loved it, really. Unfortunately, there is a moment where the journey has to stop. Now, in my case, I wouldn’t say unfortunately because through my teaching, the journey continues. I have the chance to live my passion by teaching great companies, traveling the world, meeting wonderful people, and watching many different works – and believe me, I don’t take a single day for granted!

There you have it. Even though Yannick had to retire from dancing eventually, he’s been able to share much of the insight he gained from his dancing experience with other dancers. The story of ballet is not a linear one, and Yannick’s story is a continuation of the passing down of knowledge of ballet technique and artistry to each new generation. He just happens to be especially good at it. Yannick has been very gracious with his time to those professionals with which he’s worked, including me, for giving this interview, and for coaching and encouraging me in company class. If you enjoyed this interview, scroll down and subscribe by hitting the ‘follow’ button at the bottom of the page, and feel free to continue the discussion in the comments. And if there’s still interest, there are still a few questions and answers (and an amazing photo of Yannick as a kid) that I didn’t include in either of the sections of our dialogue, and I’d be happy to release this little bonus feature if enough of you want to see it. But that’s it for now, folks. Hope to see you next time!

Great interview lucas! I also enjoyed the videos of class! Thank you!

LikeLike

Glad you liked it! Suggestions welcomed.

LikeLike

I am so enjoying Yannick’s interviews!

LikeLike

Great interview! Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

Interesting, bittersweet…

LikeLike